Kahm Yeast vs. Mould in Lacto Fermentation

Knowing the difference between them can save your precious ferment and give you the confidence to know when it's time to throw one out.

11/11/2024

Unplanned visitors to your ferment

Lacto fermentation is a fascinating process that transforms fresh ingredients into probiotic-rich, tangy delicacies. At the heart of this transformation lies a delicate ecosystem where various microbes interact, sometimes creating unexpected visitors like Kahm yeast and mould. However, for many home fermenters, the appearance of unexpected growths can cause disappointment and concern.

For someone in the early stages of their fermenting journey, looking into the jar and expecting to see beautifully transformed vegetables only to be assaulted with the vision of a landscape of microbial colonisation is a stomach churning sight.

The micro organisms creating this miniature alien forest are made up of, yeasts, bacteria and moulds.

Knowing the difference between them can save your precious ferment and give you the confidence to know when it's time to throw one out.

Understanding Kahm Yeast

Kahm yeast is often misidentified as something sinister, but it's actually a relatively harmless organism. Kahm yeast (Candida famata) is actually a type of wild yeast that thrives in fermentation environments. Unlike dangerous moulds, it's a relatively benign organism that belongs to the broader family of surface yeasts. Scientifically classified as a non-pathogenic (not harmful) wild yeast. Kahm develops when certain environmental conditions create an ideal breeding ground.

Appearance:

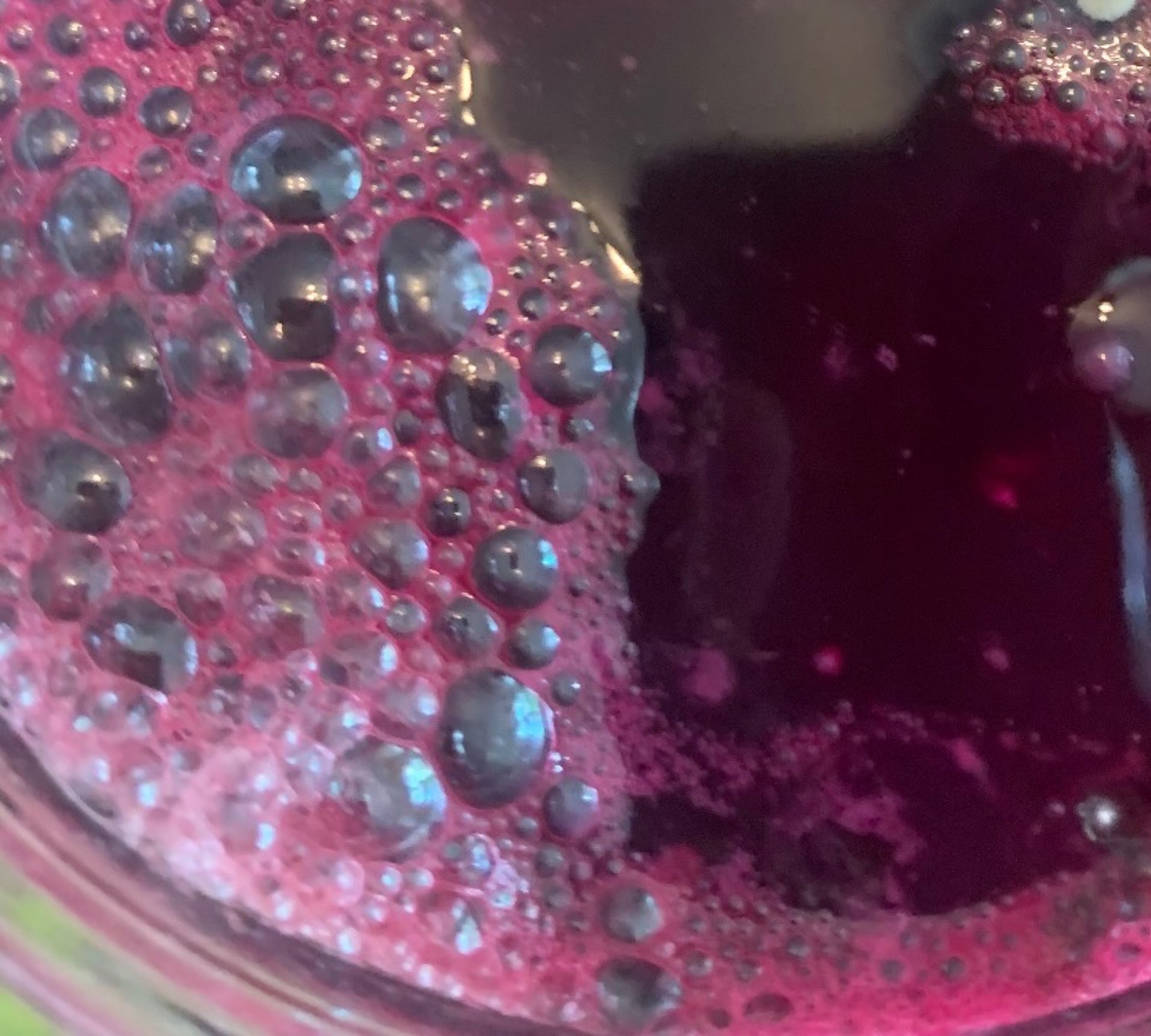

Kahm yeast typically looks like a white, thin, wrinkly film that forms on top of your ferment. It can appear dry and powdery, with a somewhat smooth or slightly textured surface. It can take on the colours of the ferment, I have had a pretty pink Kahm yeast grow on the surface of a deep red beetroot ferment.

When the yeast grows it can stop some of the gas bubbles escaping the liquid, causing little spheres of kahm covered gas.

Kahm yeast, growing on the surface and on trapped gas bubbles

Microscopic Structure:

Under a microscope, Kahm yeast appears as oval to elongated cells that form a thin, continuous layer.

Environmental Preferences:

Thrives in oxygen-rich environments,

Use a lid with an air lock to stop oxygen entering the jar.

Use the right size jar, one that doesn't leave a large amount of empty space above the brine. Too much empty space above the vegetables gives the yeast access to the oxygen it needs.

Optimal temperature range between 65-75°F (18-24°C)

Keep in a cool place during hot weather.

Prefers slightly alkaline environments with pH levels between 5.5-6.5

Nutritional Requirements:

Feeds on simple sugars

Develops in the presence of residual oxygen

Typically appears in ferments with higher sugar content or less acidic environments

If you do notice Kahn yeast growing on the surface it can be easily scooped off with a clean spoon, then remove it as more appears. It can change the flavour of the ferment, some people find it a little musty and unpleasant, some people don't mind it at all, but it still remains good and healthy to eat.

Mould growth in Fermentation

Unlike Kahm yeast, mould represents a serious biological contamination. Moulds are multicellular fungi that reproduce through microscopic spores, capable of producing mycotoxins that can be harmful to human health. Their texture is intricate and carpet like, some patches dense and almost solid, others thin and web-like, with feathery edges that blend into the brine.

Mould is a diverse group of fungi that:

Grows in multicellular thread-like structures called hyphae

Reproduces through tiny spores that float through the air

Can grow on almost any organic surface with moisture and nutrients

Exists in numerous colors including green, black, white, blue, and gray

Plays a crucial role in decomposition in natural ecosystems

Mould needs several conditions to grow:

Moisture

Warmth (typically 77-86°F / 25-30°C)

Organic material to consume

Oxygen

Darkness or low light conditions

Types of Mould

There are thousands of mould species, but some common types include:

Aspergillus: Often found in indoor environments

Penicillium: Blue-green mould, source of penicillin antibiotics

Cladosporium: Dark green or black, commonly found on plants

Alternaria: Typically dark brown or green

Stachybotrys (Black mould): Associated with potential health risks

Health Implications

Respiratory irritation

Allergic reactions

Asthma triggers

Potential production of mycotoxins ( can cause poisoning )

Mould typically appears as:

Fuzzy patches, like you find on mouldy bread

Distinct colors (green, blue, black, or white)

Raised, textured growth

Clearly defined borders of circular or irregular shapes

Unpleasant or musty odour

Why You Can't Just Scrape Off Mould from a Ferment

Mould is far more than just the visible surface growth. What you see is only the tip of the microbial iceberg. It is impossible to completely remove with surface cleaning.

Mould has microscopic root-like structures called hyphae,

These roots penetrate deep into the ferment.

Invisible to the naked eye.

Spread throughout the entire food item.

Toxin Production. These toxins can spread throughout the entire ferment.

Mycotoxins are heat-resistant and cannot be destroyed by cooking.

Identification Checklist:

Visual Inspection:

Colour: White/cream = Potentially safe

Colours like green, blue, black = Discard immediately

Texture: Smooth, powdery = Likely safe

Texture: Fuzzy, raised = Potentially dangerous

Smell Test:

Normal ferment smell = Likely safe

Musty, rotten, or extremely sour smell = Discard, well why would you want to eat it anyway

Touch Test (with clean utensil):

Easily removable white film = Probably kahm yeast

Sticky, resistant growth = Potential contamination

Be aware that you could have harmless Kahm yeast growing on the surface, with small pockets of mould forming, have a good look over the entire surface before making a decision to eat or discard.

Bacterial growth on the surface of the brine.

Something else that can grow on the surface of the brine is bacteria. Not all bacteria that appear on the surface of a lacto-ferments are cause for concern. In fact, many play crucial roles in the fermentation process:

Lactobacillus Species: These are the primary good guys of lacto-fermentation. While they primarily work throughout the ferment, some strains can form biofilms on the surface. Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus brevis are particularly adept at creating protective layers that can prevent harmful bacterial growth. Like the smooth film of the SCOBY that grows on the surface of kombucha or cider vinegar.

White Film Formations on the surface of the brine due to bacteria

Often mistaken for Kahm yeast

Can be a thin layer of protective bacterial colonies

Typically harmless if the ferment smells and tastes good

Indicates active fermentation process

Protective Bacterial Layers

Some bacterial growths actually serve as a protective barrier:

Creates a seal against oxygen

Prevents contamination

Helps regulate fermentation environment

Surface growth that are healthy indicators that all is well:

Thin, white or cream-coloured film

Consistent texture

No distinct colour changes

Mild, slightly sour smell

Warning signs that things aren't going well:

Fuzzy or raised textures

Distinct coloured patches

Unpleasant odours

Significant brine cloudiness, more than usual

Mould formation

Risk factors that give rise to the growth of mould

Improper salt concentration, too much or too little.

Incomplete vegetable submersion, use a weight to keep it all submerged.

Inconsistent fermentation temperature, usually too hot.

Contaminated equipment, sterilise your equipment if you have had a mould growth, ceramic weights can be boiled for 10 minutes, in water with some vinegar added.

Poor initial ingredient quality, the vegetables could have harboured a lot of unseen mould spores.

Your health is more important than saving a ferment. If you're uncertain, it's always safest to discard the batch. When it comes to lacto-fermentation, food safety is paramount. If you observe any signs of potential contamination—such as unusual colors (green, blue, black), fuzzy or raised surface growth, off-putting odors, or significant changes in texture—you should immediately discard the entire batch. Never taste or partially remove the suspicious area, as harmful bacteria and toxins can spread throughout the ferment, even if they're not visible. Trust your senses: if something looks, smells, or seems wrong, throw it out, your health is more important than saving a ferment.

Mould growing on a beetroot ferment

Pellicle ( gelatinous biofilm) growing in kombucha, protects the micro-organisms from external threats. So it's a good growth in your Kombucha.

Cloudiness seen in a jar of vegetables after a few days of fermenting is a good sign that things are progressing nicely.

Taradale, Victoria. Australia 3447