Understanding pH in Lacto-Fermentation

Understanding the pH scale and how to test the acid level

The Importance of Acid in Your Ferments

Lacto-fermentation is a microbial process that has been used for centuries to preserve food and enhance its nutritional value. At the core of this process lies a critical factor: knowing the acid level, or pH.

This guide provides a look at the role of pH in lacto-fermentation, its measurement, and its significance in producing safe, flavourful fermented foods.

One crucial aspect of ensuring your ferments are safe, is to monitor the acid level. This can be done by testing the pH level. Checking the acid level of your ferment is good to do when you first start fermenting. After a while you will get to know the right smell and taste and have the confidence to know when it is ready to eat, without doing any testing. A well made lacto-fermentation is safe, nutritious and harmless.

Understanding a little about the way the acid level affects the fermentation process gives you confidence to create safe, quality ferments consistently with the ability to troubleshoot the process when needed.

I recently made a carrot, garlic, ginger and chilli ferment in a 2% brine. I was after a younger crunchier ferment, so a shorter fermentation time was planned.

The jar of carrots was left in a cold part of the house for 5 days. Usually this is enough time for the acid level to drop to below 4.6, but it had been colder than usual. On opening, it had a very mild smell and the brine was still quite clear.

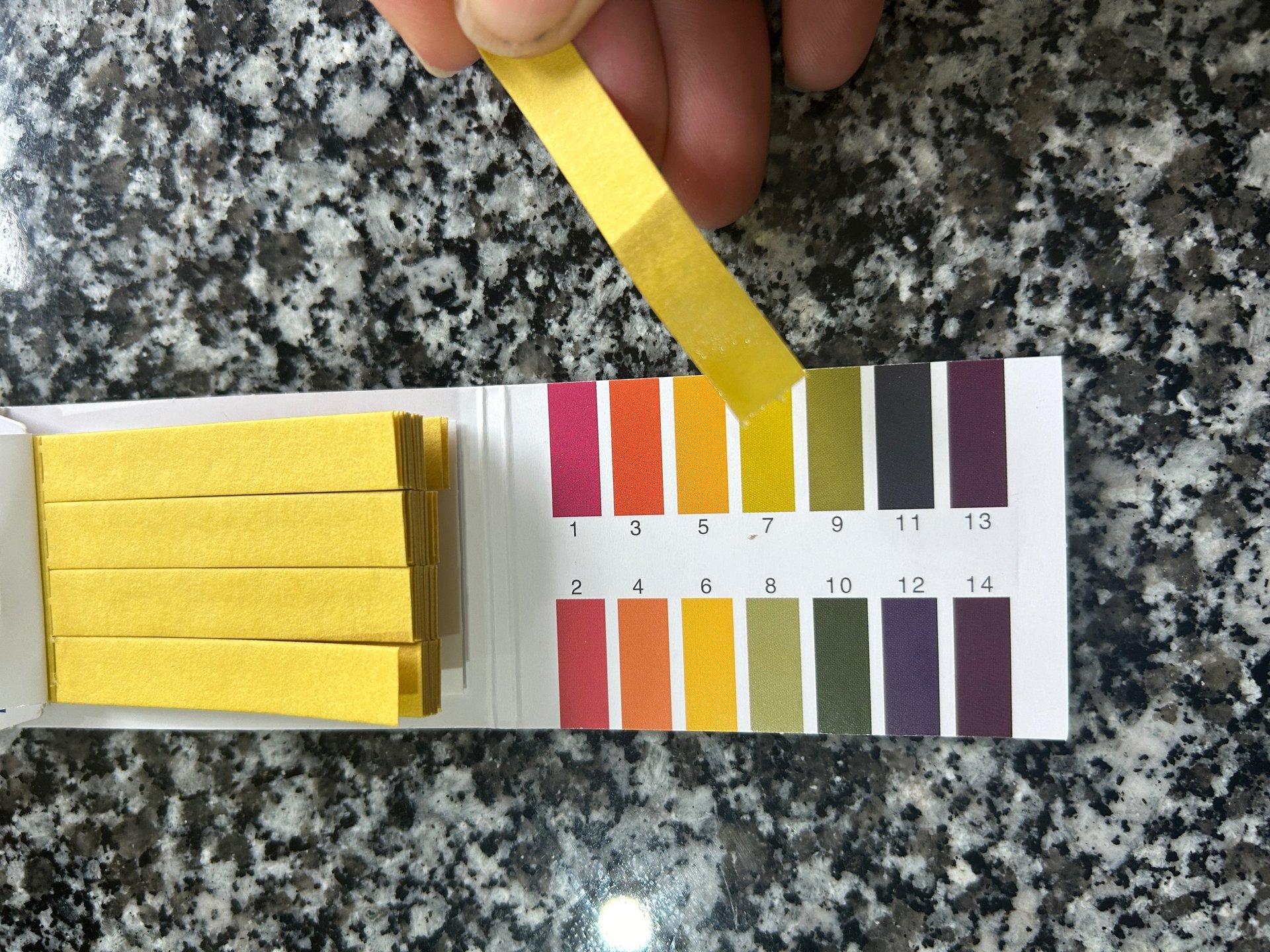

I used pH paper to test the pH, it showed that the brine was still above pH 5, telling me that it wasn’t ready to eat.

I moved it to the kitchen, to sit for another 2 days in a warmer environment. After 2 days it gave a reading of pH4 and it was showing some cloudiness, indicating it was now safe and ready to eat. Even though the right amount of time had passed the room temperature had slowed down the fermentation.

In the end, the timing is up to you. As long as the right acid level has been reached, how much longer you ferment is up to you. If you prefer soft, broken-down vegetables, then ferment for longer. If you like your vegetables crisp and aggressively tangy, stop fermentation sooner. After placing the ferment in the fridge, the fermentation process will be slowed significantly, with the acid level remaining constant.

Understanding the pH Scale

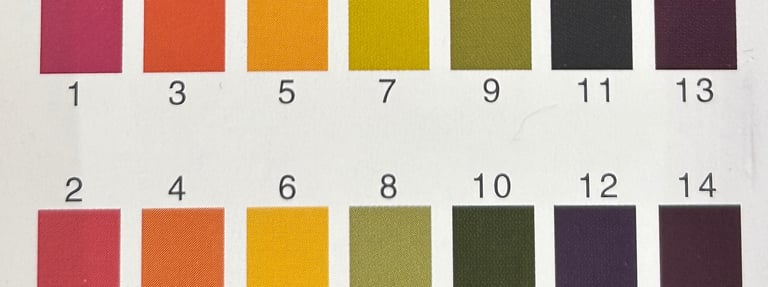

pH is a measure of acidity / alkalinity on a scale from 0 to 14.

pH of 7 is neutral, drinking water is usually neutral

pH above 7 is alkaline, sodium bicarbonate gives an alkaline result.

pH below 7 is acidic e.g. vinegar, lemon juice and kombucha.

Good verses Bad

Lactic Acid Bacteria

I will call them (LAB): These are the beneficial bacteria responsible for lacto-fermentation. They metabolize sugars, complex carbohydrates and proteins, producing lactic and acetic acid.

LAB are acidophilic (acid loving), thriving in pH ranges from 3.0 to 6.0. As LAB produce acid, they create an increasingly hostile environment for competing micro-organisms. LAB are facultative anaerobes, meaning they can survive with or without oxygen, but prefer low-oxygen environments.

This gives LAB a competitive advantage over harmful bacteria, who can’t survive in the acidic environment, creating a natural preservation system.

Harmful Bacteria:

Many harmful bacteria prefer neutral pH environments (around pH 7.0), and they struggle to survive in acidic conditions. Pathogenic bacteria like Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Listeria monocytogenes prefer neutral pH environments (around 7.0).

These bacteria struggle to thrive in acidic conditions, leading to cellular stress and eventual death of the bacteria.

The Right Acid Level

pH 4.6 is the threshold: Below 4.6 is the level we are aiming to achieve to be sure that the fermented food is safe to eat.

Clostridium botulinum (the bacterium that causes botulism, a very serious cause of food poisoning) will not grow and produce toxins below pH 4.6. Our aim is to have a ferment more acidic than 4.6, so we are sure that it is safe to eat.

Texture and Flavour

The enzymes produced by LAB function best within specific pH ranges. Maintaining the correct pH ensures these enzymes can effectively break down complex carbohydrates and proteins in the food. The acidic environment is important for the development of desired textures and flavours found in fermented food.

A ferment that is left for a long time at a pH that is too high, can result in soft and slimy vegetables.

Temperature

The rate of acid production and the final pH depends on factors such as temperature. If it is too cold, then the ferment is slow to progress or even stop. The optimal temperature range is 18-30°C, with some organisms preferring the lower temperature while others are happier at the warmer range.

Salt Concentration

Too much salt can kill the organisms, leading to no fermentation. The more salt you use, the more acidic the final taste will be, as well as being much saltier to tase. The salt also hardens the pectins in the vegetables helping to keep them crisp. A range of 1-3% salt concentration is what is commonly required to achieve a safe and delicious ferment.

Colour Changes

pH affects the structure of pigment molecules, leading to colour changes in fermented foods.

Anthocyanins, responsible for red and purple colours in fruits and vegetables, change colour based on pH. In acidic conditions, they tend to be red, while in alkaline conditions, they shift towards blue. For example, the vibrant pink colour of fermented red cabbage is pH dependent. In acidic conditions, it tends to be more red.

A change in colour of the vegetables is normal and shows that the LAB are doing their job.

Preservation Mechanism

The low pH directly inhibits the growth of many unwanted microorganisms by disrupting their cell membranes and interfering with their ability to thrive.

The acidic environment, combined with the consumption of oxygen by LAB, make conditions unfavourable for many spoilage organisms.

Flavour Profile Through Acid Balance

Different organic acids made by the fermentation of micro-organisms, contribute to the various flavours. Lactic acid provides a mild, tangy taste, while acetic acid (found in higher amounts in longer ferments) adds a sharper, vinegar-like note.

The length of time the ferment is left at room temperature influences the aroma and taste of the final product. That’s why cabbage fermented for 5 to 6 weeks has a sourer taste than cabbage fermented for only 1 week.

As the pH drops, it activates various enzymes produced by the LAB.

Pectinases break down pectin in plant cell walls, contributing to the softening of vegetables in ferments.

Proteases break proteins into peptides and free amino acids, enhancing umami flavours and contributing to the characteristic tangy taste of fermented foods.

Lipases break down fats, releasing free fatty acids that contribute to flavour complexity

Understanding these scientific principles underscores the importance of monitoring and maintaining the correct pH in lacto fermentation. It's not just about safety – it's about creating an environment where beneficial bacteria can thrive, enzymes can function optimally, and a complex array of flavours can develop.

By understanding the role of pH, you can ensure your ferments are not only safe but also delicious and nutritionally enhanced.

After a while you will get to know the right smell and taste and gain confidence to know when it is ready to eat without doing any testing.

Mineral Availability

As pH lowers, mineral salts become more soluble, increasing their bioavailability (ability to be used and absorbed by the body)

For example, the bioavailability of iron, zinc, and calcium often increases in fermented foods.

This process contributes to the enhanced nutritional profile of fermented foods, potentially improving mineral absorption in the human gut.

Troubleshooting pH Issues

When troubleshooting a pH that's not dropping in a fermentation, consider the following factors:

Salt concentration: Too much salt can inhibit beneficial bacteria growth.

Temperature: Ensure the environment is warm enough (ideally 18-24°C) for fermentation.

Oxygen exposure: Check that vegetables are fully submerged to maintain an anaerobic environment.

Sugar content: Low sugar in vegetables can slow fermentation; consider adding a small amount of sugar.

Contamination: Ensure all equipment and ingredients are clean to prevent unwanted microbes.

Time: Some ferments may take longer than expected; patience is key.

Starter culture: Adding a small amount of brine from a successful ferment can kickstart the process. Add a small amount of cabbage, it has large amounts of lactic acid producing microbes living on the leaves.

Instructions for using pH paper to check the acid level of your ferment.

You will need, pH paper strips, clean dropper or spoon, and your ferment.

Checking the pH of a ferment using pH paper strips is a simple and quick process

Take out some of the brine liquid: Use a clean dropper or spoon. Only a few ml of liquid is needed.

Apply brine to the paper strip: Place a drop of the brine onto a pH strip or dip the strip into the liquid on the teaspoon. Never dip the strip directly into the jar. You don’t want the chemicals on the pH strips getting into your fermenting food.

Wait briefly: Allow 30 seconds for the strip to change colour fully.

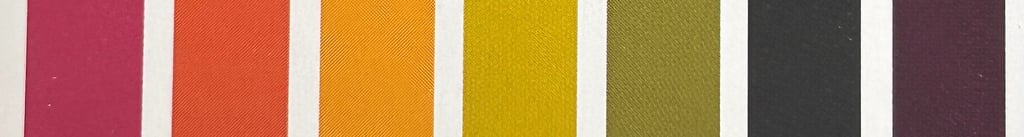

Compare the change in colour to the chart that comes with the test strips

Read pH value: Identify the pH value corresponding to the matched colour on the

chart.Record result: Note the pH value and date for future reference.

Repeat if necessary: For accuracy, you may want to test 2-3 times and take an average.

Clean up: Discard the used pH strip and rinse your dropper or spoon thoroughly.

Interpret results: Generally, a pH of 4.6 or lower is considered safe for fermented vegetables.

Remember to always use clean utensils and avoid contaminating your ferment during the testing process. Testing the pH with pH paper strips is an easy and powerful tool in creating consistent, safe, and delicious fermented foods.

Taradale, Victoria. Australia 3447